Text in pdf + Note on the middle ground at the end of the text :

Seeking stability

By Clémence Ortega Douville

Illustration 1: Cormorans by La Fille Renne

Trauma has a deep and discrete connection with failure and mourning. When the attempt of meeting fails, the continuity of the body’s existence pushes us to recreate bond with it, to find meaning again. Meaning comes because of something that is not self-evident anymore. The presence of our own body doesn’t look up to the same reality. We have lost an attempt, yet our body reminds us that we are still on the try, on one side of the river.

This essay wants to acknowledge the progress that we have made with the theory of the three paradoxes in making the foundations of the cognitive structures of our species clearer. And at the same time, we are still wondering on its outcomes. What kind of ethics should it claim from us ? Are we ready not to seek means of control and increase them, but to rethink the way we situate ourselves in those living ecosystems that we share with other species ? As many plead for a better consideration of ecofeminisms’ analysis, what we have learnt now should encourage us to validate their concerns.

The structure of trauma is then very important to consider, because it all starts with an effort to meet reality, a reality that we represent to ourselves, something in front of us, part of us but impossible to reach permanently. The hand that I see in front of me is at the same time the one that I keep. Being both, it cannot be decided as either one of them without destroying the part that I do not choose. The memory of this situation literally gives birth to imagination, and its coordination with the teaching of the presence of others, to symbolic meaning. We only partly choose what is meaningful to us.

Having a mind in human terms means that we are stuck between two possible worlds – the world that is myself and the world that is something else – and never allowed to part from this space in-between. We weave trauma as we tell stories to express this state of being at the same time actor-ress and audience to our own being seen. As long as we interpret what we see and what we suppose that is seen, we cannot choose side. We are always wandering in the breach between both. We need the other that might see us to exist in the symbolic world that we hold in stead of being there. Psychoanalysis, notably, cannot bypass the assumption that our own reality is withheld inside of its evasive fundamental nature. We will all lose in the end the thread that ties us to others. That we will let it go, is certain. That we must look forward to what remains, is better.

This essay will try, not to be explicit, but to be honest and sincere about what we think is good to be taken : the existence of the body, interpretation and language, culture and creolisation, and most of all, the cure and the care.

Voluntarily, we will favour sources from women, trans*1 and non-binary people as much as possible. Likewise, we will put forward points of view and perspectives from minorities of race and class. The reason is that sometimes, the consistency between the norm of knowledge and its social tacit contracts must be broken to admit other forms of reality, being nonetheless human.

The consistency of the telling can and must be allowed to be broken and disrupted, especially when it has been confiscated for political reasons. What the theory of the sensorimotor paradox has informed us, is that one symbolic order is always relative to the interpretation one makes over their situation toward pain. Trauma reifies pain, transforms it into a voice of our own.

The voice of trauma tries hard to steal the pain away, but is always the most powerful to dialogue with it. Discovering Agnès Dru’s work on choregraphy and her reflection around the idea of creolisation, as developed by Edouard Glissant, writer born in Martinique, made me think again about the subversive nature of the telling of trauma.

We have to acknowledge the debt. Then I think that the best way to tell the story of meaning in our human species’ evolution is to stay as close as possible to the power of trauma to upset the way that we, people, make History our own.

I – From a sensorimotor paradox to interpretation

Creolisation demands that the heterogenous elements put in relation ‘intervalue each other’, that there be no degradation or reduction of the being, either from the inside or the outside, in this contact and in this mixing. And why creolisation and not crossing ? Because creolisation is unpredictable, though one could calculate the effects of a crossing.

Edouard Gilssant, Introduction à une poétique du divers, 1995

It might seem odd that we would evoke a notion such as creolisation while making connections to a theory of anthropogenesis. Now, take that odd. What are the postulates of the three paradoxes theory ?

- We consider that a simple sensorimotor paradox due to the development of bipedal stance might have sufficed to permit the elaboration of the human cognitive structures of thinking.

- This paradox would be due to the « delay or lag » (condition of Edelman) in the motor response to sensory sollicitation (whilst I am holding my own hand in front of me in order to see it as something else than myself, I can only keep my body suspended, frozen). This delay would disconnect the production of a sensory memory from the necessity to enact a motor response ; hence, the production of pure images, at first a representation of oneself.

- Imagination would have to find its way to a proper shared social value while sharing this experience with others. The symbolic comes from shared and recurrent meaning and thus, is arbitrary and idiosyncratic to the group.

- Then, as a consequence, the relativity and conjectural nature of the norms of our knowledge, likely based on Western Sciences, must be acted.

Which means that we have all to gain in considering an extraction from a partial and situated point of view that, despite its qualities, is consitent with structures of systemic political domination.

21st century thinking cannot be other than decolonial, feminist, deductive of class analysis. As stated by intersectional feminist figures such as (but not limited to) Angela Davis, bell hooks, Colette Guillaumin or Françoise Vergès, without those dimensions, the consistency of the production of thinking with structures of political and social determination would tend to exclude a non-neglectable portion and spectrum of actual human experiences. The idea of decolonialism, born in South America in the 1990’s, states that despite the end of formal colonialism, racism – deeply connected to sexism – keeps on living as a structural motive to the unequal distribution of wealth and political power. Coloniality dictates what is proper and valid as a representation of the norm and the critique of neoliberalism would thus point out the disparities in the application of what should be an egalitarian political liberalism. However, capitalism still creates and maintains a partial ruling of its own competition doctrine (social darwinism).

The assumption that the advance of Western societies regarding its scientific, technological and legal sophistication should justify their domination over other forms of societies should on the contrary push us to deconstruct the idea that this supposed advance would be a goal in itself. Hence the ethics of knowledge in front of an imperialist doctrine. The one who knows, what do they know and what for ? How is knowledge shared and what should the ethics of right be in those exchanges ? How to identify the structures of violence in any culture without be biaised to our own ?

There would be, at the heart of any assumption of knowledge, the desire to be recognised as valid to the group. Attachment is one of the most fundamental motions guiding a human life as well as so many other species’.2 That is why the structures of society conditioning the access to legit recognition are so important to scrutinise, because the debt to those who are excluded from that legitimity would be either justified or denied by those who would benefit from it. As we made the goal to our own development conditioned by a competitive system, we would benefit from the exclusion of the contestants. Dealing with their will to exist in one way or another demands either an immediate physical repression or the setting of symbolic ties to keep the possibility of repression up as a menacing signal. (By the way, interestingly the history of virility and the taming of the male bodies to martial obedience would, according to philosopher Olivia Gazalé [Le mythe de la virilité, 2017], as far as we may know come way back from Greek and Roman’s Antiquity.3) One would just have to give another enough to lose.

Why think on the idea of creolisation then, here ? Because, as Françoise Vergès answered on an interview on France Culture, on March 8th 2019, some important notion such as feminism are in a way tagged, for example, to a cultural situation. Then to Françoise Vergès, who was raised in the island of La Réunion and lived in Algeria, the idea of ‘feminism’ was not consistent with her experience, but seemed to pertain to a white bourgeois movement and to this application of French universalism – ‘we are all French’, but in practice, some are more French, more legit than others to the title and knowing better what is best for everyone – that is colonial in essence. Education cannot define but what is understood as common as to come to the good.

This example stresses that words do have a technical meaning but also a social and a personal meaning. They have a powerful symbolic impact and we cannot be oblivious of the fact that our text, our telling our reality, will be inevitably interpreted and received differently according to the reader. Our simple being here in one social space is providing a very heterogenous variety of meanings according to whom would read it.

Our attachment, in the theory of the three paradoxes, to the sensorimotor condition to the genesis of thinking is connected with a demand to be open to this variety of interpretations to which leads the situation of each individual’s experience. The very idea of situated knowledge, promoted by feminist thinker Donna Haraway, invites us to go further into its implications to the sensorimotor paradox theory.

Nothing gets meaning outside of the stimulation of sensorimotor imaging. It is the capacity to apprehend an action and at the same time to block its enacting that situates meaning at the core of human experience. One of the conditions of the theory is that no change, no evolution in any species comes from the sky. It only comes as a co-adaptative and chance-like interaction with changing environments and as well changing as our perception and the modalities of our interaction with them change (F. Varela, E. Thompson and E. Rosch, The Embodied Mind, 1993).

Language only comes as a way to temporarily fixate our relation to our environments and the way that we situate ourselves within – I agree, it is a very ecofeminist way to tackle the issue. As our experience changes constantly, it is only a matter of wishful thinking that we would hold words and other manifestations of meaning (gestual, graphic) as faithful depictions of how we value our progress in existence amongst others. The harder we try to permanently apply those structures in a rigid way, for fear of losing grip on reality, the more we discart the callings of our own perception of it.

Words contain more than a solid truth, they contain memory that is deeply embodied in our personal history. The way that we move and perceive ourselves is marked by the situation we adapted to in order to be accepted, first as children, then as grown ups. The image that we show of ourselves in the public spaces, no matter how large, is also shaped by a variety of slight or larger traumas that determined our own personal creolisation.

The definition that we established of the trauma is that it is not that much of the shock that created the wound, but the mark left by it and the activity of healing over it. Roughly, we described it as a a + b = c equation. An object b meets a subject a (the quality of subject can be reciprocal, regardless of the intensity of the meeting) ; but after the meeting, the result is no longer one or the other but a new object that is the mark, visible or invisible, the memory of the meeting.

Further more, the possible meaning in the etymology of trauma that is ‘the defeat’ suggests its interpretative nature. It is about the response that we give away and the meaning that we have then given to the presence of this memory in our life. It is about how we tell the story of our situation in the shared world of imagination, to which we mimetically intergrate the example of others. The impact that this memory has deep down in our body drives our conduct up in discrete ways – that is why trauma can be unconsciously passed to generations.

What we have to learn from the narratives of colonial heritage and slavery is not that different from what we would have to learn from ourselves if we really tried to ask the question. What is the value of such a word, of such a knowledge in the way that one perceives themself ? Knowledge is always deeply personal. We know nothing for knowledge itself. We only situate ourselves with knowledge – don’t we dialogue with the actions of our hands and thoughts ? It should be then first consistent with the way we actually situate ourselves, logically, before to connect with more global considerations.

What we learnt from the sensorimotor paradox is that we are compulsively (to borrow from biologist Julia Serano) in demand to resolve the contradiction within itself. Our imagination is dependent on the domestication of the body at the service of the liberation of the production of images from sensorimotor enaction. The fabric of our capacity to use memory to the service of the combination of sensory imprints and their identification demands that we tell our body to be available for it, and then to stop or partialy stop to respond to our direct environments.

We progressively learn to compartmentalise our responses and their address, so that we can and must maintain a stream of thoughts – that is the representation of our conduct – and at the same time continue to interact. We are still seeking stability through this. As psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott said so elegantly, we learn to be alone in the presence of others, connecting what is not communicable (our sensory experience) with what can be through language. The sides of language depend on the other people’s interpretation : the way we move, the way we show faces (see mother-infant interactions in Ellen Dissanayake’s neuroaesthetics studies), what we ask, the attention that we ask and the way that we ask it.

All that pertain to some ‘meta-hermeneutics’, to the sensorimotor fabric of interpretation that implies that we observe ourselves progress in the representation of our own world of meaning. To the latter we connect common meanings and ideas, patterns and structures to our own traumatic experience. So it is never abstract and it is always massive, because the body is a mass of its own and should be respected.

That is why the aim of this essay is to converge to our body’s deep and rich experience, always unique, in order to situate our presomption of knowledge in the light shed by the hypothetical advance of the theory of the three paradoxes.

The idea of meta-hermeneutics came from the statement that the body is constantly subject to interpretation. It emits meaning as a feedback to the way we anticipate that it would be interpreted in time and space. That I imagine myself doing something pertains to such an anticipation. Not only meaning is sedimented in verbal language, but the total sensorimotor experience and its memory are engaged in meaning. It is always one meaningto one body.

Language works with two main qualities and operators : analogy and combination. To make language out of something requires only to give it meaning in reference to a normative setting ; hence, the expectation and anticipation, which requires to be aware of whole formalised narrative patterns (Paul Ricœur, Temps et récit, 1983). A norm is always a measuring tool, as to its mathematical definition. I see my own hand that I hold in front of me, then I am situated as a subject relatively to this state of tension to my own hand. I create time and space relatively to that measure. Between the two is the norm that conditions interpretation – that means, the practice of analogies and combinations from a set of elementary notions and references.

Language is structural. Its speaking and writing are only the emerged and visible, the communicable aspects of it. But its structure leans on the whole commitment of the body to its sensorimotricity and the channeling of memory. That is why we started with trauma, because trauma is holding the line, it is demanding attention and arousing concern and care. Trauma roots our emotional resources in the experience and memory of the body and creates a norm for itself. When this memory is triggered, there is a signal for a response, that is how the living works. Trauma is sensory and memory and it creates an object that was unknown before. Trauma, either slight or large, creates the reactualisation of our relation to the world. It creates new conditions for it. We interpret our situation because of trauma.

Yet, contrarily to most species, the voluntary use of those memories, their modularisation, formalisation, combination and generalisation are due to a measure of control on our own capacity to produce images : that means, to produce new memories, to forge them out of the compilation of sedimented and articulated meaning. But again, what makes language here is not only that, but the fact that we constitute the conditions so it could be shared with someone else. Language needs mutuality, then it needs conventions. It needs a shared norm to which each member of the group would comply to make a minimal understanding.

Thus, the way I move would in itself not constitute a language but only as it would eventually anticipate someone else’s interpretation. Then I would conduct my movements to what I suppose would be a convention and a norm for meaning. You would find analogy (I compare myself to the norm) and combination (I adjust heterogenous elements and cues to a consistent normed ensemble). The way I walk is a sedimented compilation of such an internalised social control on how the body should be read in the shared space.4

The capacity to voluntarily recall oneself to the situation of being observed and having to adjust to the others’ gaze is provided with the capacity to hold the body from its actual situation in space and time, and to create a controlled new norm for experience in which the emotional resources are everything. When the sensorimotor paradox of the gazed hand, emotions become central and it resonates with our position in-between (like the mirror phase in psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s theory). As Ellen Dissanayake stated, the body imprint in the (proto-)aesthetic experience is primary to its semantics :

‘If one considers the temporal arts, it is clear that not all arts are symbolic— for instance vocalizing or playing a musical instrument, marking beats, or dancing. Their effects are emotional more than cognitive-symbolic: they attract attention, sustain interest, and create and mold emotion. Visual marks need not automatically be assumed to be representational, as in the earliest drawings of children and, arguably, the earliest rock markings of our ancestors. On the contrary, these are traces of marking as an activity in its own right, having an effect on the world and making the ordinary surface extraordinary. Aesthetic operations of regularizing or formalizing, repeating, exaggerating, and elaborating these marks are additionally interesting and satisfying, even when they are not symbolic.’5

It of course depends on the definition that we make of the symbolic. In the more lacanian sense, it would mean something that constitutes a sedimented meaning, a substitution ; but also a tension to something lost inthetranslation. The notion of symbolic is consistent with the collective inscription and handling of trauma and the idea of nost-algia, ‘the pain of the return’, the latter being impossible. We take the symbol for something else.

In fact, the discrepancy between the sedimented memory and its representation creates a tension to what is impossible to transform. You cannot transform something that is in something that was – in the same way that you can’t decide whether this hand is the one that you hold or the one that you gaze, which cannot be simultaneous. The sensorimotor paradox, which would be theoretically founding the cognitive structures of our species, makes it very difficult to situate the place of the subject. Is it in the tension to the object I hold my attention to or in the fact that, holding the object, I am also holding my own self participating to a moment of intense relation ? As to shared traumatic experiences (in the large sense including basic sensory experiences), we collectively try to withhold what social interactions can’t or don’t allow to express and how much trauma can be written in shared spaces.

But as it would be rooted in the sensorimotor paradox with our hands, it would not be illogical to think imagination as simulating the response that hasn’t been actualised.6 An image is always perceived as a substitution, an analogy for something that the body would experience. To mentally hold an image is not that much different from actually holding it with our hands. – The situation is transposed, but isn’t it the same with symbolic inscription ? The less it is expressed, the more it relies on this tension to anticipate the response that would be given at least as a substitutive image.

Ellen Dissanayake situates the nest of the proto-aesthetic process in the mother-infant early interactions – involving repetition, formalisation and ritualisation in order to draw attention. Of course, the theory of the sensorimotor paradox is mostly relevent in an anthropogenealogical perspective, to mark the turn between some of the common structures between mammal species and what makes the specificity of ours. Then the environments in which individuals are born change progressively.

The early encounters and interactions that a human infant makes today are radically different to those of our prime ancestors. The conducts get progressively codified, taught to be conform to a collective norm for mutual interpretation. Again, evolution is always fully interactive and by adapting our means to relate to our environments, we make our perspectives toward them evolve ; as well for those surrounding us.

A world with humans is radically different for any species to adapt to than a world without. Yet, the proscriptive way of analysing evolution proposed by biologist Francisco Varela – stating that less than seeking optimal adaptation, species would only have to find stability as long as some critical situations, endangering survival and procreation, would be successfully avoided – enables us to think meaning as something that most of the time escapes moral prescription and encapsulation, as well in the field of language. The foundings of psychoanalysis rely on this idea that something in the body’s experience is unprescriptible, irreducible and escapes but its own normalisation.

Allegedly, the idea of a sensorimotor paradox resolves the aporia by determining a most probable point to what is irreducible in the experience of (self-)consciousness. We are enthusiastic as to capacity that it offers to consider symbolic experience as a result of an embodied co-adaptative setting for long-term evolution.

Once learnt how to experience such a thing as distancing imagination from the body’s response and emerging the emotional resources for self-consciousness, it only has to be stabilised in time, and repeated over and over in the same way that we continually speak to ourselves in our own minds.

But what is a paradox in the first place, and most of all a sensorimotor one ? A paradox is a rupture in logics. Roughly, it is saying that a = b with b ≠ a. You would summon an equivalence between two objects that are radically unidentical or incompatible. A paradox is an attempt to make coexist two entities that structurally cannot, like two opposite magnets.

In the terms of the sensorimotor paradox, it means that the object of my own hand cannot be at the same time the mean to achieve an action and the manifestation of a still object that I would focus on. Sensorimotricity implies that I would be aware of the presence of my hand in space and time to my senses ; yet it is not the same thing than to want and summon it to stay right in front of me as if it would not be coordinated to me anymore.

Each time I interact with my surrounding environments, sensorimotricity means the way that my movements and my senses constantly coordinate together in order to make those interactions, to enact possibilities offered by them. We learn from what we discover that we can do with what is surrounding us. With the development of bipedal stance, our hands got more and more liberty to express new ways of interacting and at the same time, a special dedication to grasping things, as well as a certain idleness whenever they are not used. Far from the nose and mouth, our relation to surrounding things is more and more mediated by the specialisation of our hands.

That means that whenever I would hold my own hand in front of me as to see what it is, the attention it would catch from me to stare at it momentarily freezes my whole body to be attentive. The hand is no longer the mean to interaction, it is the object of a possible interaction in and with itself. I summon the fixity of two parties, making coexist two impossible things : a hand that would and would not be mine, a body that would likely be to resume interaction but frozen to its object.

The possibility to make this relation exist and to keep it still pushes the subject into subjugation, for the otherness quality of this hand cannot be fully extracted from the concrete reality of its being part of my own body. Two kinds of reality come to coexist in the same object : being or not being me, something ‘other than me’ to the control of my body. So I can control something other than me, the image of a thing there, through the stillness and focus of my body. Therefore again, the paradox opens the way to an impossible solution that I envision as a crush in something that should be logical.

If anything goes right and sensorimotricity keeps on cycling, I am not to be conscious of its nature. Its disruption, in another hand, makes me aware of the structure that supports it. Experience becomes other than self-evident as I shift my perspective. The world around me becomes a question as the previous modalities of my interactions with it came to disruption. I am exposed as a body with an experience, as this same experience got exposed by being cut from the necessity of its tie to sensorimotricity.

The paradox is that I can come back and forth yet cannot stay but in-between, because my experience is nevertheless rooted in sensorimotor condition. The paradox is a moment when I identify to the image that has been produced. More than that, I identify to the relation I made to it, to the extraordinary tension that it provoked. But also, the artificial character of this situation indicates that it requires a voluntary commitment. The deep personal connection that I would make with such a relation exposes the quality of the subject as I become one to myself. I become an experience separated from the rest. I ‘discommit’, to borrow from philosopher Etienne Bimbenet.7

A paradox has a dazing quality that discombobulates as one cannot find the usual path between elements. Something of the sublime is contained, reminding of what is laying in the unknown. Most of horrific literature rely on displaying anomalies in the fabric of the usual sense of reality, such as in H. P. Lovecraft’s short stories. If the latter wrote his stories out of a very deep sense of xenophobia that has to be inspected, criticised and contextualised, it is interesting to value the precedent he set to Western imagination.

Most of the time, first person scientific record is employed to make the anomaly concrete in contrast to a firm establishment of rational thinking. The characters are reluctant to say what they experienced as being too radical and irrational to be taken for granted. But has imagination not this quality of being set in total breaking from ordinary experience of reality and then, pushing us to create new connections beyond our cultural inscription, between the world that we live in andthis secondary strange layout of transformed memory imprints ? In fact, it seems to make sense that we constantly make correspondence between what we are to experience in the present moment and the stabilisation of images that we use to rely on, to make sense from the very destabilisation of reality. Because we have to make some sense out of them, in the same way that a person experiencing psychosis would try to make sense out of a disruption in the experience of reality (Darian Leader, What is madness ?, 2011).

Further more, one thing that the sensorimotor paradox introduces is a rising entropy. The activity of the body is mostly cyclic and constantly has to renew itself while the paradox, introducing a disruption in the cycle, forces attention to a straight connection. While the body is put on hold, its internal energy still produced is also waiting for resuming its resolution and transformation.

So the paradox creates stillness and the fixation of an artificial state. It creates a linear perspective to a sole problem : how to get out of it ? Again, it marks trauma as something that cannot be resolved but only bypassed, resumed to the normal activity of the body. The attachment to what was represented and emotionally charged but not recovered would be a strong motive to anguish and depression. Nostalgia is a fundamental drive.

But the image cannot be eternally fixed, for the body is always cycling. Like in Arundhati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things (1996), life gets circling around the stillness of trauma, erasing the traces and covering it up with new memories. Yet the effort to recover from a wound creates blank spots as we refuse and deny access to experiences that might revive the pain. What it forbids us pushes us to new adaptations.

The way that we relate to our environments, to others and our own body is not solely determined by our traumas but the detours that we take to avoid it while it is still trying our attention. Likewise in the sensorimotor paradox, it is not the paradox in itself that may have driven our thoughts to the evolution of the human mind but in fact, all the ways that we bypassed its impossibility in order to make sense out of our experience of the world again.

An interesting parallel can be made with psychoanalytic literature, when Jacques Lacan evokes Sigmund Freud’s work from Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920), in his seventh seminary on the Ethics of Psychoanalysis. Let us quote :

‘This is [the primary drive to experience reality] what Freud points out to us when he says that the primary goal and the closest to the test of reality is not to find in real perception an object that would correspond to what the subject represents to themselves at the time, but it is to find it again, to testify to oneself that it is still present in reality.

[…] This is without a doubt a course of control, of reference, according to what ? – to the world of their desire. They make proof that something, after all, is really there that, to a certain extent, may be useful. […] This object will be there when all the conditions will be fulfilled, in the end – of course, it is clear that what it is about to be found cannot be found. It is of its nature that the object is lost as it is. It will be never found again. Something is there in the meantime, if not something better or worse, but in the meantime.

The Freudian world, that means the one of our experience, includes that this is this object, das Ding, as an absolute Other of the subject, that it is about to find.’8

For what we may be cautious of about the context of creation of both Freudian and Lacanian’s theory9, there is this thing in common that we can connect to our analysis. According to Jacques Lacan, ‘the necessity to speak ideas, to articulate them, introduces between them an order that often is artificial.’10 This, in Lacanian theory, corresponds to the chain of the signifier, that we may understand now as a consequence of the incapacity to resolve the founding sensorimotor paradox. The entropy and ‘the structure of experience accumulated’, all the memory that has not been followed by a resolution in their enaction, is condemned to swirl and to find ways in and out on their own.

It is interesting to view language as a certain way not to interact but to recreate the movement of possible interactions from a distance, to recreate scenes that would match convenient patterns. We are made the subject of an experience of not being able to resolve a situation that should have been. We have to maintain it open. We are are made subject of an impossibility and it is quite crual to be made a subject, because we are put at the centre of an irresolution and become the object of a desperate seek for it to be resolved nonetheless.

For one thing, the sensorimotor paradox allowed us (if confirmed) to gather a sense of ourselves being remotely connected to things around us and a sense of ourselves for its own sake. The first idea when it came to it was to analyse the correspondence we could have made between the distant connection to our own hand and the one symbolically situating objects around us for our own reference. Again, analogy and combination. This tree there maybe is not that different from me and my hand, maybe they are equivalent, maybe I can grasp the idea that this tree would have an answer for me to the problem of my hand.

Suddenly, I can rely on those things surrounding me as to release the discomfort of being suddenly me and only me. Nothing else can be expected from this moment, yet it compulsively cannot just be useless – it has to be meaningful on the contrary. We ask from the things surrounding us an answer to the anxiety of being resourceless in front of our own emotions. There is all to wager that the beginnings of our thinking should have possessed something of a madness. To quote Darian Leader, there is ‘a difference between being mad and going mad’. The intensification of the relation to reality would have given quite an insolent power to those things around us, and we must say that thinking in itself, if not supported by convention, is very close to what we call psychosis. To interpret their being there when we feel so confused would have likely been in fact the early moments of mystical reading and finding meaning in the world whenever it made no sense anymore.

We become subject by becoming an object to a world of meaning (that sometimes pushes us to reappropriate what is offensive to us). Only convention separates the subject from the world that creates them. This way we interpret ourselves as demanding support from a knowing world, for we suppose that there is some consistence in a world that seems to stand so well when we can barely know what is happening to us. Whenever we receive this support, it is good to be, otherwise, we are not so sure.

That also has to do with the very structure of trauma, as we perceive the other that is touching us as a force that is pushed on us in their otherness, that we have to make our own – not much as a subject, but as an alien object (so is the paradoxical hand). That is why it is always about the narrative of how we are left in the world after meeting the other. We talked about slight trauma because the cause of trauma doesn’t have to be massive in itself to constitue an experience. The touch of a leaf falling on our arm is a trauma. It is a contact, and we try to give meaning if not to the leaf itself, at least to the moment and scene where the experience happened with something other than us.

It is very important to remember that from the moment we adjusted to a situation where we learnt that we could in fact not respond while being virtually able to – the ‘virtually being paradoxical –, we could summon this control over ourselves to wonder about the very possibility that things would happen to us as we would be the centre of a world of meaning.

For a centre to be, an inertia has to be set. From that inertia, we would decide of the value and necessity of a response or we could simply be at the centre and see what would happen to us. We would likely give priority and motion to what would come to be surrounding us rather than necessarily resume our busy focused life.

Then the strangeness of our own hand moving can become as fascinating as any other creature’s. To borrow from Ellen Dissanayake again, the ordinary can become extra-ordinary simply by charging with the intensity of our affective demand for a relation to the world. But who or what is going to take charge of meaning and the organisation of time and space in this time being ? What is going to drive and modulate our attention ?

The formalisation of speech has a lot to do with the thinning of body activity at the heart of the paradoxical sensorimotor suspension. We are always in and out of sensorimotricity as we summon our memories and at the same time have to send the signal to others and the world that we are still setting the course of a dialogue. The support that we seek from our environments is for releasing the anxiety of being pointless at the moment when the paradoxical state founding our conduct is not derived to a distraction.

In fact, if we stay still, we are vulnerable to attacks or any contact. The anxiety of suspending the body in its sensorimotricity is that what’s around us is still happening, including the risk that somebody or something would cut us from our moment and demand a response from us that would have become less than obvious. Stillness has to be codified as to guarantee a safe space around us. Hence giving meaning to the world and mapping reality as a minimal measure of control.

It is dangerous to stop and think. Literally, it was and is when we would start to question whether to run or wonder. We wouldn’t chase a rabbit but may be struck by the flash of its running through the bush. What the other does that we can’t do would maybe start to appear more familiar in the strangeness of our own feelings. At least something is running through while we cannot decide where our feet are.

At last, we start to read things as if they were a clue to our own extension. We would have to measure the distance from our disability to determine ourselves. ‘What is it asking from me ?’ And the other one that is like me, what does they want from me if I am made unabled to respond ? And what is the alternative ?

Interstingly, in a conversation with writers Marci Blackman and Darnell Moore called « From Pain to Power » on The New School, October 7th 2015, writer and scholar bell hooks refers to psychoanalyst Alice Miller by saying that ‘the abused child can survive if they have a witness. In the sense that the witness becomes the person that offers you a different sense of yourself.’ Alice Miller wrote that ‘our body does never lie’ and in the same way, it connects to the definition that Jacques Lacan gives of the real as ‘what you would always find again at the same place’11 and the symbolic being circling around it.

What does come to stop the blankness of the state of paradox that would constitute the basis of an availability for thinking ? Something has to drive us out of the stupor that the sensorimotor paradox would provoke, and it should be true that the idea of a third party between us and ourselves would offer this other perspective. Because the state of paradox is a restraint and it is intense and painful in an unique way. Coming from the outside, the other may be a thread to catch in order to find back the track to shared reality. Maybe the gaze of this other one, this witness, would be a solution to my being stuck. Maybe the interaction with them is how I take back on the course of something that would luckily prove uninterrupted.

Because it is an interruption, basically, this paradox, and the body doesn’t like to be so radically stopped in its rolling on. Yet again, something exists in the state of paradox that does not otherwise : the possibility to relate to something that is impossible to grasp, to take and understand. That is this quality of mystery, of not being connected, the gap in the chain of the signifier, that makes the salt and taste for what is utterly unknown. The sensorimotor paradox is, literally, the invention of the unknown – because we ask something from our disability to act our own body out of its radical exhibition. We are paradoxically to be both ourselves and the urge to get out of this moment of capture.

From a world where only stimulation and response exist, suddenly comes the unrelated, the encagement of reality inside of the owner of a body. The paradox makes no sense, it has no direction anymore for it is directed at itself, but it is utter and sheer presence to something that we cannot fathom for we cannot act to it – just step back and literally ‘get out’ of the loop. There is this sense of being plunged in gravity, frozen into a bath of overwhelming sensations. What is taking hold of us that we cannot but try to go beyond its hold on us, for it is uneasy to feel frozen and caught, powerless and at the same time, ourselves the source of this intense relation.

It has something to do with this idea of philosopher Gilles Deleuze that the ‘invisible is what can only be seen, and the unspeakable what can only be spoken’.12 What is unrelated is at the core of the symbolic system as a break-up from sensorimotricity in order to produce an image and then a series of images chained together in order to avoid the impossibility to crack the paradox.

It is very important to see that the idea of a sensorimotor paradox permits us to understand why the rooting of the symbolic is so difficult to apprehend, because it is a limit-point of the body revolving on itself. As an initial symbolic trauma, it may certainly have set the course of a remodelling of reality and the modalities through which to perceive and enact our being situated here and never alone with ourselves.

II – Playing balance : the covering up of trauma

And who shall separate the dust

What later we shall be :

Whose keen discerning eye will scan

And solve the mystery ?

Georgia Douglas Johnson, Common dust

A good example of covering up trauma is in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag series (2016). Her character seems to be constantly avoiding the expression of trauma while in the same time she is determined to meet people and push them to some exposure. She comes as a mass of erratic impulses, trying to connect but not knowing how, only knowing that no one would be supposed to say things in the open. So she doesn’t speak the trauma, but she provokes people to constantly remind it to the viewer. She would not say how annoying her step-mother is but she would steal the statuette in her office. She doesn’t judge others as much as she questions how much attention they would pay to her and thus she sets the boundaries of trauma around her, according to the resistance of others to address it.

In an incredible way, the series shows someone who witnesses the covering up of trauma under substitutive conventions, but as she keeps quiet about her revolt against it, her whole body being here nonetheless seems desperate to tell it out. So there is a violence in morality, in the way conventional moral laws not only forbid certain things but prescribe a standard conduct. As we leant on philosopher Paul Ricœur statement ‘because there is the violence, there is the morals’13, we returned the corollary : ‘because there is the morals, there is the violence’. Violence is the conditioning of aggressiveness inside of the restraint of moral laws. They create boundaries even before the individuals could comprehend and analyse the reason why as to form an adequate ethics about it.

Therefore our interactions with the social spaces and in the world of meaning are conditioned by favoured or inhibited conducts. Some areas of those concrete or mental spaces are greyed by the incapacity to relate to them, because it would not be accepted and one would be considered distracted from the correct path. We then assumed in earlier work that collective rights should be decided in an awareness of political and social constructs and in respect of each other’s right to self-determination, support and consent. That is why individuals and groups should be able to claim up their own narratives according to local shared experience, in relation to structural political settings.

Quite recently, in France, singer and actress Camelia Jordana, born in Toulon from Algerian parents and grand-parents who first came to France in the 1950’s, has spoken up for herself and those who don’t feel safe in front of police officers, supposed to protect the population. Though her testimony is supported by an official study by Défenseur des Droits stating that young people (especially young men) of colour are more likely to be checked by the police than other parts of the population (2017), the young woman is now to suffer a public and mediatic backlash. She was definitely not supposed to say that, for an artist from immigrant descent should be grateful to come to publicity, even as a token for an apparent pledge of diversity. What is not spoken is of course that such a system of political power that we find in France and elsewhere got to pile up over systems of domination, notably colonial but also internal, and that the collective trauma that the national narrative built upon cannot be addressed nor reckoned as still structuring our society.

The history of France is not just ‘there was the Colonial Era’ at some point and then, over, we turned the page. It is the history of all the people in the Caribbean, on the African and Asian continents that it has immersed into the district of its meaning. Those people have to respond to it and many of their voices are not heard or made audible and valued. We make some people in debt for having been accepted on our territory while we have built some of our geopolitical influence on the exploitation and coercition of theirs in the first place. One stated very eloquently : ‘before you tell someone to go back to their country, ask who went to whose first.’

So there is this language of control that makes the living of many people precarious as the guarantee of legit belonging is not given. There is this repeated shock over the same wound, ‘you are not legit’ as black, brown or asian people, as a woman would be compared to a man that is supposed to be more rational, as a person with handicap, a LGBTQIA+ person, body non-conforming, lower-class, etc. The articulation of those people’s situation in public speech is not widely spread, so those persons have to constantly explain it again and then personally commit themselves to set the dialogue around their own personal and shared trauma.

By depriving someone from the collective nature of their speech, making it neglectable and only reliant on their vulnerable individuality, though it is recurrent and systemic, you can crush this experience and make the conditions for their legit speech precarious. Trauma will try out different possible narratives depending on the difficulty to access the direct zone of the pain. It needs time to progressively nest the interpreted story of the trauma around the origin of the pain.

When you repeatedly push the person or group to relive the very situation that caused it so they can’t elaborate a multi-directional perspective around, you create a system of domination. When it is collectively addressed, trauma can virtually be addressed with everyone. So time and space are not closing down on the person or group like it is still the case for most people now. And we do not value this symbolic oppression as much as we should. It in fact makes very different possibilities of life from a same apparent setting of reality.

Why bell hooks evoked this idea of Alice Miller’s that you need a witness to elaborate trauma and survive, is probably that you need to elaborate a map of your rights. With no outter gaze to escape a narrowing duality, you are blocked – same with the hand paradox. The legitimacy to exist and have access to conscious public speech and expression is also affecting the possibility for the body to occupy spaces. Again, we can take up sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s idea that ‘the legitimacy of symbolic violence necessarily depends on the legitimacy of physical violence’14, that notably the State (which is a fiction for the consistency of the actual political structures) uses to maintain its domination though apparently providing people with some liberty.

What happens on a macroscopic scale is yet not that different from what happens more locally. In another of her conferences, bell hooks comes back with actress Laverne Cox (on The New School, october 2014) on the idea that beyond the self-acheivement of their respective careers, it is still about the journey to that point that isn’t shown in the words or images of their respective books or films. It is very relevant to the question of trauma, because what we knit from trauma to our narrative is still very different from the vivid experience that cannot be told. (Bell hooks also makes a very relevant point about the way White people care about the idea of safe space, which is not that self-evident if you are yourself living anyway with a sense of anxiety caused by a racist, classist and sexist division of society – that is why she prefers to talk about ‘being comfortable with risk’.)

There again, we find back this dimension of trauma that makes something communicable from something that is not, something collective borrowing many voices from something deeply personal and intimate that pushes the person on to their emotional boundaries. So what could be their collective boundaries and how much personal space can sanctuarise within them ?

Pain forces us to draw attention to the sensory surface on which it pressures. It polarises the way that we perceive reality for a moment or for a while. The work of trauma is to first put some grey on the surface in order to cover it up with other colours and reorganise our perception of time and space and what we can do with them. So now we are going to address the way that we do elaborate trauma and how it may be relevant to the idea and practice of the cure.

‘It is far away the time of the beginning of the war, when the militiamen of Sigüenza refused the rich cooking of the barracks, because they only wanted to feed on ham and chicken. This memory sets in front of me the image of Hippo, draws in the dark his eyes of light, brings back to my ears his indulgent words : « To them the ham is a revenge ; in Spain the poor could not buy ham. »

Tears run from my eyes. This is the first time since his death that I cry this way, isolated in the dark, for myself alone, freely, with great sobbing, hidden in the corner of a door, away from anyone’s gaze, in all weakness.

I must go back as soon as possible to the front, the rear is no good to me. My days here will fill up with discouraging images, I will have too many useless leasures, too many nights haunted by all the dead stayed behind me. I can be of service only in action, I feel incapable of assuming other tasks than those of the war itself. And I accepted to survive Hippo only on the condition that I continue our fight.’15

In her personal story and memories of the Spanish War of 1936, Mika Etchebéhère tells us about the complicated role she had to play to the militiamen under siege. When her husband dies on the front, she becomes a ‘mother of war’ to the heterogenous variety of men, most with no experience of the war, who came and joined the trotskist column of the POUM.

‘I don’t have, like the militiamen, the right to hang out in bars to shorten the days and nights without fights. My status of fearless woman without blame, of special woman, forbids me to. So do my personal convictions.’16 She earlier explained that it was the only way for her to put some distance with the potential lust of men who would be otherwise tempted. Then she has to maintain a certain irreproachable conduct for herself in order to be respected as a person and not consumed as an object of desire.

This conduct also constitutes a way for her to stay focused on a temporality consistent with her possibilities of action, preventing her from collapsing with grief and sorrow. The moment of pain that she describes when she finally lets herself go with her feelings of loss, alone in the streets of a constantly bombed Madrid, tells us something about the distinction of trauma compared to its original pain : one cannot change what caused the pain, but they can change the narrative of trauma.

Why is the nature of collective representations so important ? Why do so many people, from yesterday to now, act to make people aware and change the way that we represent ourselves as a society ? Mostly because if you cannot allow people with pain to nurrish a narrative that would lead to a reconfiguration of possibilities, you simply push them to keep stuck there, crushed under the weight with no means to make their own voice heard.

Trauma covers up the pain of the constant return to things that cannot be changed anymore, and to do that it has to reshape the form reality would take to the person. They have then to be able to believe that other worlds are possible, other ways of relating to others, to recreate a network of values in which they would be able to find balance and play it.

When a flesh wound, the process of healing would require to leave the wound alone, and then over the scar something new might happen. The mark is still there but it can be interpreted as a mark, as something of which the radical openness has been decided toward one of the possibilities that it offered to deal with, when chosen the world of meaning in which to do that.

The world in which Mika Etchebéhère could count on the presence of her husband to justify that she would be there fighting has gone, as well as the possibility to see him again. So she has to lean on the possibilities that the collective mind permits her to enact in order to still be perceived as a person in her own right. She has to play on the symbolic binary representation of women as being either the virgin, the mother or the whore. Eventually she has to repress a huge spectrum of what she could do or express so she would not fall from one determination to the other.

What was true for a woman in the 1930’s is not less true today, even if it took various other forms and at the same time encountered progress in some ways. We all have to chose directions at different moments in our lives. If we expect to find resistance in the way that who we are would be interpreted in social spaces, how does it map our own representation and perception of the world surrounding us ?

There is a picture I like very much by La Fille Renne, who is a gender non-conforming photographer working with argentic cameras, which represents a group of black birds (that I assume to be cormorants) taking flight on a rocky shore. The whole thing is a bit stern and does have a gloomy touch but at the same time, there is this flight and the group from which we tend to predict the following of a global movement altogether. It is not one bird, but the sense that the first one would gather a chain of others, all alike and all individuals at the same time, from which we would draw expectations and consequences.

Here again we have a fine and moving depiction of trauma. Something is leaving us to be alone (the first bird), but as we come to expect that the others will follow and that there would be a chain of cause and consequence to which we might be able to participate, it stimulates the movement to join, to identify to what is common to us in this form – individualities gathering into something consistent together.

Trauma is something very strong because it draws consequence as radically different from the cause. The whole picture changes as the object changes. It is not the bird leaving anymore, it is the group. It is not the wound, but the scar. It is not the loss of someone you loved, it is your own dignity in front of adversity. It is not the infamy of slavery, it is the transformation of language and music and dance through creolisation.

The first shock provoked a scene that could only last for a moment of meeting and pain, either slight or large. The scene of contact created something blank around the point of the shock, a stimulation too intense to focus on anything else. Pain obsesses attention and paralyses it. Like the sensorimotor paradox, it creates an impossibility to relate to it, mostly because it belongs to the two parts of the meeting over the region where the contact happens. It cannot be accessed nor born and sustained with attention, that has to be driven to a second circle around while it is healing.

We cannot participate actively to the healing in fact, because driving attention to it would only make it harder, because we cannot change it. The wound has its own inertia. What we can do is bring balance all around the second zone from the wound and progressively prepare to the aftermath of the scarred wound, to elaborate the narrative, the world of interpretation that would create past over something that was, to draw consequences from the mark – from loneliness to an offer toward the collective space. Like History, trauma works in layers. The problem is when the wound is constantly reopened and we cannot tell stories anymore and thus, new realities, because we are too busy with the pain to figure out a way not to be alone.

The reflection around La Fille Renne’s photograph echoes with another of bell hooks’s conferences (I sware that I am no official promoter), this time with writer and activist Chirlaine McCray. They talk about the sense of fragmentation and dissociation of identity according to the different social spaces that one would have to adapt to (especially when this effort would be as radical as Black and other discriminated people would have to suffer). The question she asks is ‘how to bring those pieces together and emerge as a whole self ?’ Both women agree on the statement that ‘you don’t heal in isolation’.

Here again, the reflection started on this photograph of cormorants taking flight gives us a clue that is that pain discoordinates our selves into pieces. Pain is pressuring a point in the body and soul around which nothing can relate anymore except to the pain itself. Pain is what can only be felt and too intensly. However the mind, on its side, is still looking for an overall coordination. It wants to act as if the whole body was available to a response. As we got used to resort to imagination in order to relay whatever we can’t or won’t enact physically, the best way to counter pain is to acknowledge the place of its being, the zone and intimacy that it pushes us to, the isolation that it requires for itself to disrelate. But we cannot disrelate ourselves or we drawn. That is why we need the chain, another track to follow, step by step, sequencing time and space through a global new trajectory that we anticipate the form. We interpret the latter from this very anticipation.

We haven’t quite tackled yet the importance of bipedal stance as to the pattern sequencing induced by walking, that means that the sensorimotor structures and modalities of our enaction to our various environments. If imagination resorts to sensorimotor memory imprints, combining analogies, the formalisation and articulation of meaning and our progress to it will be consistent with the global perception of our sensorimotor interactions and their emotional entailments.

There is an analogy made between the sense of physically participating to our reality and the emotional feeling of not enacting but imagining and displacing them. As Ellen Dissanayake stated, attention to movement doesn’t have to be symbolically related but it still pertains to a syntax of emotion, playing with the balance between tension and resolution and how the body responds to them. What shows the group of birds ready to follow the head of the chain is that the perception and anticipation of a movement that would leave a trail, a mark and draw a line restablishes this in-between tying the whole and the parts together. We participate to the whole through its sequencing that would induce a patterned rhythm to its movement, something articulated.

It is relevant in music where the sense of the beat or its annihilation would ease or not the sequencing of time consistently with the tapping of our feet. As well, this back and forth between tension and resolution has been a motive to progressive deconstruction in modern Western written music since Gustav Mahler to spectral music and later on with concrete and electronic compositions – from formal syntax to the formalisation of movement. But we could also join the very keen analysis of comedy made by Hannah Gadsby in her show Nanette (2018), where she explains to the audience how she would create tension and hold it until a release.

Again, what pertains to the symbolic and language in all that is the perpetual control over the way people situate themselves to others and their own body. To see one bird flying away is not the same thing as witnessing the take flight of a group. For on one hand, the isolation of one’s own individuality would be soften by the dispersion of attention to the group. Attention would synthesise the discrepencies in the gathering of individuals into the more global form of the group itself. And on the other hand, because to imagine oneself joining the collective effort would blur the perception of their own body and identify in a multi-directional way to the plurality of angles through which to perceive a shared identity. (That is the disturbing element with cubism, for instance, because the plurality of angles disrupts the linearity of how one would perceive the contours of identity. But it is the same with Hannah Gadsby when she introduces, for a moment of tension, a doubt in the liability of the speaker to their audience.)

So it goes with trauma, because pain breaks the continuum in the perception of time and space as to the continuity of the body, and the activity of trauma would try to recreate this sense of a whole, of identity out of this shattering. That is why again, as it would remind us of the example given by Darian Leader of a woman rolling herself in plastic tape in order to mend the feeling of her body threatening to break into pieces, the breaking point of psychosis, for example, is deeply continuous to the same stucture of how trauma works. And that is why so many racialised people reclaim their right, today, for the recognition of their traumas and the consequences on their psyche in a system of oppression.

(By the way, bell hooks considers love as the best foundation to heal, combining care, commitment, responsability, respect and trust, in partnership and/or friendship – so, I leave it here.)

‘The birds sang in chorus first,’ said Rhoda. ‘Now the scullery door is unbarred. Off they fly. Off they fly like a fling of seed. But one sings by the bedroom window alone.’

Virginia Woolf, The Waves, 1931

In an interview given to Self, Laverne Cox explains : ‘For me, personally, my body matters. How I exist in this body, feel in this body, is really important.’17 A clue that this idea of the channelling of trauma, in order to recreate a continuity through fragmentation, gave us is that indeed, facing the elaboration of trauma needs some kind of sustainability and support.

On a TED Talk on vulnerability (2019), social worker Brené Brown went to the first definition of the word ‘courage’ (instead of ‘bravery’), in order to understand better how some people would manage to get along with vulnerability and embrace it. She found out that it came from the Latin cor, that means ‘heart’, and that it originally meant ‘to tell the story of who you are with your whole heart’.

Now remember the Greek etymology of trauma, that meant ‘the wound’ but could also mean ‘the defeat’. Trauma is a shock wave, but not the shock itself, that is a concentration point, deeply localised and non-communicable. Trauma, as we saw, is the story-making over the wound. But trauma may or may not be actively supported by an act of courage. To ‘tell the story of who you are with your whole heart’, you have to support the story that you would lean your relation to others on.

That means that this way for you to tell your own story situates your self in the world of meaning that you wish to share with others. That means that sometimes, you have to transform the direct symbolic environments that you live in (family, social spaces, society) into one that would be fit to you inner self and to the story and voice that you would spontaneously be to carry and offer and share.

Hence, when Laverne Cox speaks of the importance of her body to her, she speaks of how she would make the way she looks as truthful as possible to her story, that she would be the most spontaneous and free to tell about herself whole-heartedly. This can apply to gender as well as to anything else. The question is : are you a better person telling that story this way more than another ? Because to tell a story is to tell a direction. For as we saw, the sense of a story is consistent with the sense of formalisation and context. It gives us what to expect, even if it goes to the unexpected. It is not making that story up. It is just adjusting the way to tell it – and there gestual and self-graphic communication are a form of language, pertaining to the telling of the story – to the way to best embody its meaning whenever it is about the meaning of your own self. It is setting the ethics from which a dialogue could be initiated with others in respect of each other’s self-determination.

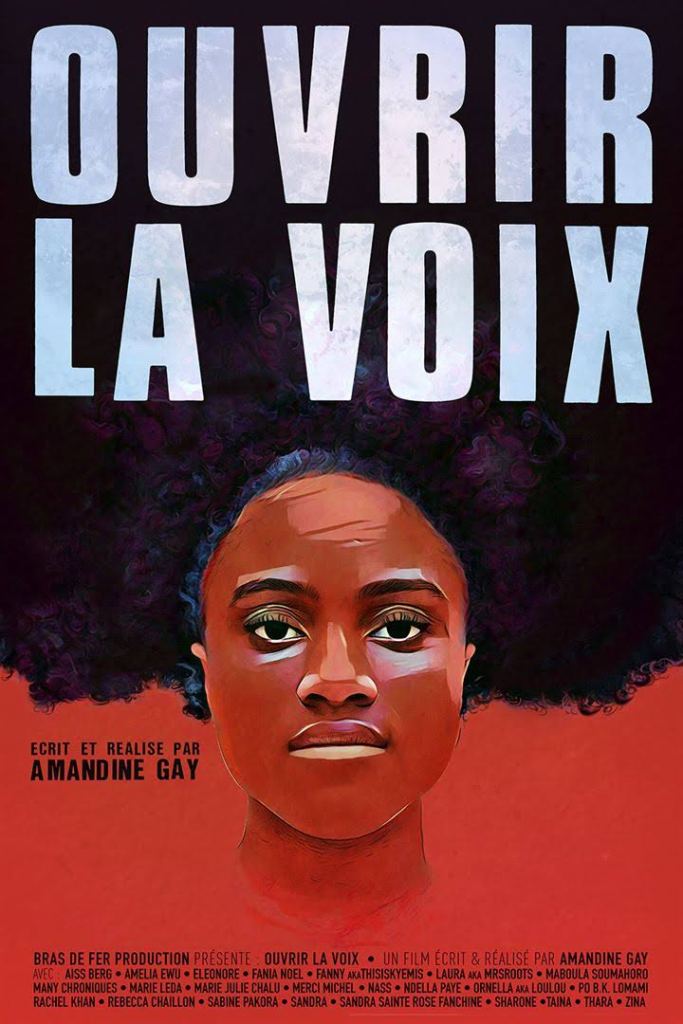

Lately, we are witnessing the uprising of Black people against police violence. In France, Assa Traoré is fighting so that justice would be given back after the death of her brother from the same systemic violence. How to tell one’s story from collective trauma and oppression ? How to sort individual voices from that ? Director Amandine Gay released a documentary film in 2017 called Ouvrir la voix, that shows 23 women speaking of their experience as Black women in France, from colonial history in the African continent and the Antilles. It is striking that many of them would struggle in order to situate themselves amongst a series of stereotyped injunctions both as Black and women, out or even inside their own community.

But what is interesting is the question of the voice, how and to whom the authority of speech is usually given ? The answer, of course, is mostly to standing class heterosexual White men as a political system. This is not prejudice to say that. It is statistics. According to the INSEE, in 2014, women represented 21% of the salaried managers in France and 35% of managers owning their own business.18 This does not include yet racial statistics, neither does it include other discriminatory criteriums such as those hindering for instance lower-class, LGBTQIA+ people or people with disabilities.

So the question of whose voices and speech do we hear the most and are more likely to have moral advantage over others is crucial in order to understand why a person such as Laverne Cox would have to struggle with inner injunctions, memories and reminiscence of people bringing her down. Indeed, she would have to select more appropriate voices and daily narratives that would on the contrary allow her to sustain trauma and elaborate her own valid story with courage.

So it is important to consider that to tell a story of one’s own sometimes necessitates to reshape the mental environments in which one lives with theirselves while living in an actual world that is oppressive to them – to be able to be alone in the presence of others in any term. How, through telling the trauma with courage, one can rethink and reshape the way they actually face others without behing ashamed of who they are ?

‘The strong smell of the kitchen cuts my breath off. The smoke and the human smells created a solid and blackish mass that is painful to cross. Someone hands me to the tip of a knife half a grilled toast, trickling with rancid butter and sugar. I thank and say that I’ll eat later, without explaining that an invincible nausea has filled my mouth with salty saliva that costs me to swallow back. A mouthful of eau de vie calms my stomach. Half a glass helps me sleep.’

Mika Etchebéhère, Ma Guerre d’Espagne à moi, 1976

So many questioned what a room is to a person. Virginia Woolf did. Bell hooks does frequently, speaking of her home as being a comforting haven full of familiar objects. Journalist Mona Chollet wrote an essay called Chez soi, ‘Home’ (2015). Mika Etchebéhère evoked the cohabitation with militiamen on the trenches of la Pinada de Húmera, facing the cold, the mud and material precarity – as well as the tacit contract of mutual protection with her fellow fighters in such a dire situation, that forced her to embody the figure of the exceptional woman.

Where are we to be the exception that sets a singularity for oneself, and when are we to measure that our identity is setting a mapping of what we hope that we can do while others are being around ? One of the reasons why we inspected the large spectrum of body expression and situation as an act of language is that the conduct of the body is responding to a topology. This topology is socially and symbolically learnt through morals in the development of the individuals.

As Donald Winnicott said, we learn to be alone in the presence of others, we learn to set a distance between the others and us that permits to evaluate the permission to move and to what extent we can or cannot move – where, when, how, what for and in the presence of whom ? We have to behave according to a taught normed conduct, to be minding the consent of others, whether they are minding ours and our well-being or not. So we do learn to create the room that we are allowed to occupy and to displace.

Body expression pertains to the identification of this room that we carry with us amongst others. The first thing checked is whether or not this safe distance is respected and respects others’. The sense of the space taken by one’s self amongst others is not neutral but as much dependant on a history of gender, race, class and validity as much as the rest. In France, Laura Nsafou and Barbara Brun addressed the issue of the stigmatisation of Black hair in their comic book Comme un million de papillons noirs (2018), that is one example of how notably Black women are taught since their childhood that their hair should not take space and drive attention to them. In another conversation with bell hooks19, filmmaker Shola Lynch told the reconfiguration of her four year-old daughter’s imagination when she released the trailer of the movie she had made on Angela Davis. She describes how her daughter took up Angela Davis’ Afro hair for herself, switching up from the previous princess idealisation fed through mainstream imagery.

Those are some examples of what it means to take some room for oneself. As well, in her film Parched (2015), Indian director Leena Yadav shows how four young women get to recreate a room of their own through a community of experience, in a society that is deeply harsh to women. In another context, Syrian qanun player Maya Youssef told me on an interview for Deuxième Page webzine20 that sometimes, while walking in the streets, she had some flash of memories of the Damascus that she knew before the bombings. There the access to a room that would feel like a whole, that would feel like home, is being denied by trauma.

On one hand, trauma creates a proximity with something that is lost, but also sets a distance to finding it again, because it revives the pain. Some of the topics of the cure are about deconstructing all the cumulated layers of meaning, the saturation of space around the wound in order to access the zone where it took place and when, to acknowledge its situation as well as the distance that one could take from it then. To situate the wound that created the trauma and name it is the most diffidult part of the cure because of the accumulation of corollary rooms that it has colonised with its topology.

As we were moving from trauma, we were also prevented from the surrounding room that it infected with pain, and thus a whole range of the expression of our self that could not be enacted in the corresponding spaces. To identify the location of the wound and the room that it prevented us from accessing may allow us to approach this location by another angle, to create a new situation for a similar location – but in another space and time. Even a trauma connected to a specific place would confront the reminiscence of memories but acknowledge at the same time that this is not the exact same place, that the return to the exact same place and time is impossible, that time created a distance that may now play for us – or not, like in the end of Marjane Satrapi’s film Persepolis (2007) and Marjane’s impossible return to Iran.

What we learnt from the first definition of the word courage is that next to the deconstruction of trauma through its telling, would come the setting of new conditions for the future. Trauma is over-localised in the personal, in the non-communicable experience of pain, whether slight or large. It still situates the sensitivity of the person. But what would they be to choose to offer others in the spaces that they share ? What would they be the most truthful to themselves to put in the middle ground between them and anybody else ? How would they ‘tell the story of who they are with their whole heart’, if not best, at least well enough ?

It is interesting that bell hooks would put love at the centre of her work, because love is a commitment to what we share with others. Anyone could and should have their room of their own, so a dialogue could happen in full consent, according to what we put in the middle to observe together and rejoice on, to find common ground. It does not happen without willingly making it happen. We have to situate ourselves at a chosen distance from others that would allow each part to observe not only what has been offered to sharing, but the quality of the relation itself.

In their tender comic book La Fille dans l’Ecran (2019), Manon Desveaux and Lou Lubie share pages to tell the story of a growing love between two women, one living in France, the other in Canada, despite the distance. That is a precious story because it reminds the reader that love – whatever form and relation it might take – can be discrete and made out of small mutual and progressive accords in finding one space for another in their lives.

Living on the same planet and finding a room for oneself is not easy, especially because space is saturated with debt and shrinking to the isolation of people into boxes, whether symbolic or literal. The next and last part of this essay will be about how to elaborate the cure in such a context and why our cultural representations are so important to help define the rooms that anyone should be allowed to take for themselves.

III – Declarative Culture

“I’m writing for black people, in the same way that Tolstoy was not writing for me, a 14-year-old coloured girl from Lorain, Ohio. I don’t have to apologise or consider myself limited because I don’t [write about white people] – which is not absolutely true, there are lots of white people in my books. The point is not having the white critic sit on your shoulder and approve it.”

Toni Morrison, interview for The Guardian, April 25th 2015

In his book Testo Junkie, philosopher Paul B. Preciado provocatively stated in his analysis of biopolitics : ‘The process of isolation and technical production of hormones permits to establish a cartography of disciplinary sexopolitical spaces and localises there the different institutions of reclusion and control of feminity and masculinity as technical enclaves of gender production. […] A great part of the clinical tests of hormones [have been practiced] in colonial enclaves (the pill, for instance, was tested on the Black population of Puerto Rico), in psychiatric enclaves (homosexuals and transsexuals were declared mentally ill and submitted to violent surgical and hormonal protocoles), inside penitential and correctional walls, and so until the hormonal technics could be absorbed by the daily anonymity of domestic spaces and schools. [They could be] introduced in an intentional and deliberate manner in a human body as [biopolitical entities and] realities attached to an ensemble of institutions, converted in language, image, product, capital, collective desire. That is how they came to me.’21

If Preciado’s approach is radical, it is interesting as to the theory of information it leans on and develops. Injected on one part of the body, hormones would have an effect on some other part(s). This reaction remotely informs us of the autonomous trajectory of the fluid. There is, according to the philosopher, a symbolic consistency between the elaboration of modern and technological capitalism and the blurring of concrete boundaries induced by the fluidity and acceleration of information and its uses – what bell hooks would call ‘the uses of imagination’.